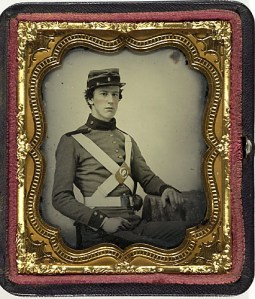

On June 18th, 1863, the 496 men of the 13th New York State National Guard were ordered to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania during the Confederate invasion. They were commanded by Colonel John Woodward. The men were ordered to pack knapsacks and wear their grey fatigue uniform. Their grey uniform was very similar in appearance to the famous 7th New York State National Guard’s uniform. As the men marched through Brooklyn for their second campaign of the Civil War, they were hailed by its citizens. Arriving at the train depot, the men traveled in cattle cars to Philadelphia and from there to Harrisburg.

On June 20th, the 13th New York SNG arrived at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania where they were mustered into U.S. military service. By June 23rd, the 13th New York SNG began working on the defenses of FortWashington. They put down their muskets and picked up axes, shovels and picks, and began clearing the woods surrounding FortWashington to prevent them from providing shelter or cover for the approaching Confederate army. As the soldiers worked on the entrenchments of Fort Washington, they saw thousands of refugees fleeing into the city in the wake of the approaching Confederates.

As the 13th New York SNG worked on the fort, their camp was located along the crown of a high hill, which overlooked the Susquehanna River. The hill sloped toward the bank of the river. The camp of the 23rd New York State National Guard was located next to the 13th SNG, and those men cut a pad into the side of the hill to level their tents. However, Colonel Woodward recalled his regiment’s camp: “Tents are therefore uncomfortably slanting, and the men are obliged to dig their toe-nails in deep to keep themselves from sliding out of their tents at night.”

Just as many other New York National Guard regiments serving in Pennsylvania, the 13th New York SNG was viewed as the invader rather than the defenders of the city. The negative feeling that they were unskilled and inefficient soldiers was viewed by many, however, the prompt and vigorous soldiers would prove themselves as effective men during the Pennsylvania Campaign.

On June 25th, the 13th New York SNG was ordered out to Camp Crook at Fenwick, several miles from Fort Washington for picket duty. By 8:15 pm, the men were under arms with one wool blanket, and one rubber gum blanket, and had moved out of Fort Washington. By 10:30 pm, they reached their designation. They were told that General Charles Yates was engaged and getting “pounded,” but upon arrival, the general was sleeping. When he awoke, he was surprised and had no idea of what to do with another regiment. The 13th New York SNG was ordered into the cattle cars of the train and went to sleep for the night.

The next day, the men awoke with no rations. They sent out foraging parties to the local farms in the area and brought back what little food they could find. By 11:00 am, the men were ordered to the picket line. There, they remained all day in the woods. Upon relief, they marched back to their camp, where soldiers of the 12th New York State National Guard provided them with some rations. By 4:00 pm, Colonel Woodward was ordered back to Harrisburg for supplies for his regiment. He was given six wagons, which were loaded up with rations and supplies. Due to the lack of room, he was forced to leave the regiment’s knapsacks behind. He started out for Fenwick. Upon arrival, he found his regiment back on the picket line at the edge of a wooded area.

During the night, rain had fallen and the soldiers were soaked to the bone. Tents and shelter halves were still about a mile behind the colonel, leaving the regiment exposed to the cold rain that fell during the night.

By daylight of June 27th, Colonel Woodward began issuing shelter halves to his regiment. The men made their camp in the wooded plot as the rain fell during the day. All the run-off of the rain made the area a mud hole. Colonel Woodward recalled: “The tents improved our condition only as would an umbrella that of a man in a bath-tub with the shower-bath turned on.” To help dry out their clothes, the 13th New York SNG built bon-fires that burned all day. By 6:00 pm, the rain slacked off to a drizzle. By night fall, worn out from the day, the men quickly fell asleep, but the conditions of the ground they slept upon was much like a swamp. Sometime during the day, the wagon containing the men’s knapsacks and overcoats had arrived from Fort Washington.

By 8:00 am of the morning of the 28th, Colonel Woodward addressed his regiment for an outstanding job. Since arriving in Pennsylvania, not one man had complained. The regiment had been in a line of battle for about forty hours resting in short doses before being ordered for another task.

As the sun shined during the late morning, Colonel Woodward scouted the area while his regiment dried their clothes. The men were wearing a mix batch of their messmates clothing due to the heavy rain that fell during the day before. Once tattoo was sounded, and after cleaning themselves up, the men went into their tents for a good night’s rest.

At 11:30 pm, the 13th New York SNG was awoken and ordered to General Yates’ headquarters. The men were ordered on detach duty for the night. One company was ordered to garrison an earthwork made of railroad ties and sandbags. Two other companies were ordered to garrison an earthenwork composed of piles of rocks on a high hill commanding a back road. By 2:00 am of the 29th, Colonel Woodward and a guide was ordered out with two companies to obstruct a side road leading through Miller’s Gap, west of Harrisburg.

The march up Blue Mountain was steep and already obstructed. The tired detachment of men under Colonel Woodward was exhausted and could no longer keep up with him. Colonel Woodward ordered his men to halt while he and the guide rode ahead. The men were unable to keep up because of three nights worth of picket duty, and another assignment given by General Yates.

After halting his men and riding ahead, with no luck on finding this road through Miller’s Gap, Colonel Woodward turned to his guide and gave him “a dose” of tongue lashing. The colonel turned around and headed back to where he left his men. Upon arrival, he found the men fast asleep in the roadway. He got them up and headed back to CampFenwick, arriving there around 6:00 am. By 7:00 am, the colonel found General Yates still sleeping in his headquarters. Colonel Woodward took personal charge and responsibility of ordering his exhausted regiment back to CampCrook, Fenwick. The men spent the rest of the day resting and were left undisturbed by General Yates.

On June 30th, there were no signs of the Confederate army near, or coming to Fenwick. All the mountain gaps located along the northern tier of South Mountain and Blue Mountain, near Harrisburg, were barricaded by blasting rocks and felling trees along the roadways. For any Confederate force moving toward Harrisburg along these roads it would be a slow and tedious process. However, sounds of cannonading at Oyster Point were heard by the soldiers of the 13th New York SNG as Confederate General Albert Jenkins and his brigade of cavalry skirmished with portions of General Ewan’s brigade of militia. This Confederate force, along with General Richard Ewell’s Corps was ordered to withdraw from this area of south-central Pennsylvania and begin moving to Gettysburg, where Confederate General Robert E. Lee wanted to concentrate his army. The next day, the Battle of Gettysburg would erupt.

As the first day’s battle at Gettysburg raged, the men of the 13th New York SNG cleaned up the camp. During the day, they held company drills and ended their day with dress parade. During the afternoon, General JEB Stuart and his cavalry were in the area of Carlisle. During the evening, the Confederates sent a dispatch to General William Smith to surrender the town. General Smith refused and the Confederate artillery opened fire. However, Stuart learned that a battle near Gettysburg had erupted earlier that day, and withdrew from Carlisle after torching the barracks.

While there was Confederate activity in the area, several portions of the New York State National Guard were detailed out. At Fenwick, Colonel Woodward received orders at 11:00 pm to break camp and march back to FortWashington. By 12:30 am on July 2nd, the 13th New York SNG began their march, and by early morning reached Fort Washington. The men broke ranks and by 6:30 am, were sound asleep using the tents of the 23rd New York SNG, who were detached to Carlisle.

As morning came on July 3rd, the 13th New York SNG awoke and cleaned up their camps. Colonel Woodward anticipated that orders would be issued by nightfall to move out. During the day, he ordered Company E to detach service in light marching orders and well armed. They were to march to the railroad and protect the workers while they made repairs to the tracks.

By 11:00 pm, orders from headquarters came. They stated that the 13th New York SNG was to prepare to move out in light marching orders. The men were to carry one blanket, haversack of available rations, and their canteens. They were to be ready to move out by 2:00 am to the railroad bound for Carlisle.

The 13th New York SNG arrived in Carlisle just after 7:00 am. About five hours later, they were ordered to move through South Mountain via Mount Holly Springs. During the day, the march was easily made toward Mount Holly Springs until a terrible rainstorm blew in from the west. Soon the rain fell in torrents. The men marched a few miles and took refuge inside of a large barn. Staying there for a few moments, orders came to move on. After marching a few miles, the men took refuge in the woods surrounding the mountain. By 10:00 pm, orders to bivouac were issued and the men were forced to sleep in the muddy road as the rain fell all night. Colonel Woodward sarcastically wrote home in a letter on July 6th, “I slept very well, never better.” The rainstorm that occurred during the night of July 4th-5th, would be a topic written in great detail by the New York State National Guard in several unit histories.

The next morning on July 5th, the march resumed around 9:00 am with no rations. The march brought them to Pine Grove Forge. There they were halted and the men wasted no time in finding food. They confiscated flour from the locality there and mixed it with water. Soon after a paste was made, they baked it on their tin plates and ate that for breakfast.

At 2:00 pm, orders were issued to move out. They would take the road leading toward Bendersville and from there to Newman’s Gap, near Cashtown Gap. After a grueling five mile march, the 13th New York SNG was ordered to halt. The men took to the woods and bivouacked there for the night. During the evening, the rain again picked up, making the conditions even worse.

By 7:00 am the next morning, the 13th New York SNG was on the march. The weather had begun to clear, and the roads began to dry out. As the men marched, more and more Confederate deserters were found and taken prisoner. Colonel Woodward even escorted a few to headquarters. For being in the wilderness, cold and wet, and without any food, the men of the 13th New York SNG were in good spirits. However, Colonel Woodward recalled feeling ill since leaving Pine Grove Forge, and took time to show his feelings toward the conditions in which he was in. He wrote, “Am now well, never felt better in my life, hungry, wet as a rat; having forded a dozen streams boots hang tight to my legs, overcoat weighs fifty pounds.” The march continued throughout the day. By 10:00 pm, a halt was ordered and the men soon fell out. They found a plot of woods and fell asleep after an exhausting day.

On the morning of July 7th, the 13th New York SNG woke up and by 8:00 am, they began a ten mile march. After marching for five miles, they came to Newman’s Gap, situated on the Chambersburg Pike. The men were given one day’s rations consisting of hardtack. Soon a steer was butchered and the men were given a meat ration to eat as well.

By 3:00 pm, the 13thNew York began their march again, descending down SouthMountain toward Caledonia and Greenwood. Once they arrived at Greenwood, they marched due south on the Waynesboro Road to Mont Alto. There, the soldiers were ordered to camp and broke ranks. The men were exhausted.

The 13th New York SNG bivouacked in the woods near the West Branch of the Antietam Creek. By 10:00 pm, the rain began to fall in torrents. The saturated ground could not hold back the water flow and soon the banks of the Antietam Creek began to overflow. It washed out fire pits and nearly drowned several sleeping members of the 13th New York SNG. Needless to say, the night was hideous and miserable.

During the morning of July 8th, the rain continued to fall until 11:00 am. By 12:00 pm, as skies began to clear, the men began to march toward Waynesboro, where the rear of the Confederate army had passed a day before. By 7:00 pm, the 13th New York SNG had made its way into Waynesboro. Once there, they were ordered to the south to establish camp on a high hill facing toward Leitersburg, Maryland and the Mason Dixon Line. The area consisted of open fields and woods. The 13thNew York, while in battle line, was supported by a battery. As they made their camp, they were located toward the rear of their division under the command of General William Smith. It was a pleasant place for a camp.

For the next two days, the men of the 13th New York SNG remained stationary. The quartermaster arrived with their baggage. While enjoying the down time, many of the men took time to clean themselves up while others performed camp duties or looked for food. No passes were issued to any of the men to head into Waynesboro. About two miles to their front was the Antietam Creek, and the charred remains of a wooden bridge that the rearguard of Confederate army had burned. The Confederate army was only a few miles to their front near Leitersburg, Maryland.

On July 11th, the 13th New York SNG was still encamped near Waynesboro. During the day, the men received full rations for the first time since July 3rd. Up until July 11th, the men had to “beg or buy” whatever food they could find. Colonel Woodward noted that his men were in poor condition for another march. However, in the same paragraph to a letter to his father, wrote, “Health of the regiment is not good as it was, but it is not bad.”

Orders came, and by 8:00 pm, the men began to march toward Leitersburg, fording the Antietam Creek, and marching over the Mason Dixon Line. By 10:30 pm, a halt was made near Leitersburg. The New York State National Guard would spend the night bivouacked in a clover field.

At 4:00 am, on July 12th, the 13th New York SNG was up and on the march. They counter marched back to Leitersburg and took the road leading to Cavetown. The men were rationless. During the afternoon, the skies began to show signs of bad weather moving in, and this storm was going to be severe. As the men were marching during the day, straggling became a huge issue for Colonel Woodward. Just moments before the storm hit, he recalled marching with about seventy-five of his men. The rest were located in front and in rear of the column. Seeing an open clover field with a small brook running through, Colonel Woodward ordered a halt.

Shortly, after 2:00 pm the storm hit with intense lightning, thunder, wind, and rain. Whatever soldiers Colonel Woodward had left, quickly buttoned shelter halves together and the men pitched their tents and took refuge under them. Unfortunately, that was of little use as the rain blew into the tents from the open sides, and the men quickly wrapped their rubber gum blankets around themselves and squatted on the ground trying to keep dry.

As the storm raged, the majority of the New York State National Guardsmen of General William Smith’s Division was about a half mile ahead, just outside of Cavetown. General Smith sent couriers back to Colonel Woodward and ordered him to bring up his regiment, but his regiment was scattered all about. Located in the open field were about twenty-five men. Colonel Woodward decided to wait out the storm, or at least the worst of it before concentrating his regiment and moving onward. He later found out that some of his regiment made it to Cavetown, and were “buying or stealing food.”

By early evening the storm subsided, and many of the men of the 13th New York SNG made their way into Cavetown, although their camp was located just outside of town limits. The New Yorkers saw few secessionists, and many of the New Yorkers were “growling” about their treatment. “Darn militia are not worth anything anyhow” wrote Colonel Woodward during his experience there. In the same letter to his father, Colonel Woodward recalled: “However, it does seem hard to make as many sacrifices as we have and then, when here, to be snubbed and maltreated. The three-years’ troops who are all here have everything.” It seemed as the colonel began to force blame onto Cavetown for the malnourished troops under his command.

Upon leaving Waynesboro, another issue came into play. The men carried everything in their knapsacks strung upon their backs during these long grueling marches and counter marches. They carried a canteen and eating utensils in their haversacks with no rations in them. The lack of food began to break down discipline. During the evening as Colonel Woodward waited out the storm, he noted that the lack of camp guards allowed the men to come and go as freely as they pleased.

Colonel Woodward also penned about his brigade commander General Joseph Knipe. The colonel seems to take up issue, as did many other New Yorkers under the brigade commander’s command. Colonel Woodward even saw General Knipe strike down a teamster upon the wagon. Colonel Woodward noted that General Kinpe had some sort of grudge against the New Yorkers. He had threatened to give them hell, and Colonel Woodward, as well as other New York regimental commanders, all agreed that he had succeeded. As night came, with the ground being wet, and the soldiers cold from being wet, they began to tear down the worm fences for firewood.

By 8:00 am on July 13th, the men of the 13thNew York began their march to Boonsboro. Rain, again, fell during the day. The men halted between Boonsboro and Cavetown, and went into camp. They built fires anticipating rations being issued, but none came.

By 6:00 pm, the 13th New York SNG was ordered, along with its brigade, to march to Boonsboro. By 10:00 pm, the men halted a short distance beyond town and made their camp in an open “stony” field. As the men looked upon the area, they quickly realized that they were surrounded by the campfires of the veteran soldiers of the Army of the Potomac.

The next morning, the 13th New York SNG was issued small portions of beef and one barrel of flour. By 11:00 am, General Knipe’s brigade was on the march, heading toward Hagerstown. Soon orders came to halt the column. By early evening, Colonel Woodward heard that the Confederate army had made its escape across the Potomac River. As the evening wore on, rumors of the draft riots in New York were heard and the men began anticipating orders for a return to their home state.

Early in the morning on July 15th, all New York State National Guardsmen serving in the Army of the Potomac were ordered to march to Frederick, Maryland at once. The 13th New York SNG began marching toward SouthMountain, and crossed at Turner’s Gap into MiddletownValley. From there, they would march through Middletown, and up, and over the CatoctinMountain at Braddock’s Gap to enter Frederick in the late evening. There, they were ordered to Monocacy Junction, where they would bivouac for the night.

The next morning, the men waited on the train that would take them to Baltimore, Maryland, and then homeward bound. By the 17th of July, the men were in Baltimore and waited for the train to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. By July 21st, the men were officially mustered out of U.S. military service, ending their campaign in Pennsylvania and Maryland.

Resources:

Kennedy, Elijah, R. John B. Woodward, a biographical memoir, by Elijah R. Kennedy. New York: De Vinne Press, 1897.