With Memorial Day approaching, it is important for us to take a moment to look back and give honor to the men and women who fought and died for this country protecting our very freedoms. Memorial Day was first established for honoring the Union soldier who perished during the Civil War. For the last several editions of the “Civil War Dairy,” I have shared first hand accounts from soldiers of Cole’s Cavalry as well as other units who fought in the Civil War. While it’s important to look at the events of the past, this month I want to focus on the importance of educating and interpreting Civil War history to the public and to give you, the reader an idea of what a living historian does. Many people are unaware that the so called “Reenactment hobby” has different categories and are oblivious to the significance of each.

The first and perhaps most widely known category is what most people refer to as a reenactment with battle re-enactors. At a typical reenactment you will see hundreds of dressed reenactors who participate in mock battles. These reenactments typically only portray how a particular battle unfolded. As spectators at a reenactment, you can visit the camps where the soldiers spend their weekend, but keep in mind this is not an accurate portrayal of how military camps were organized. Nonetheless, attending a reenactment from a spectator point of view can be fun for the entire family, but often very expensive.

The second and lesser known category is living history encampments with living historian interpreters. This is what you see when you visit Antietam National Battlefield, South Mountain Maryland State Park or Gettysburg National Military Park. The main objective of a living historian is to educate the public through various interpreter programs, providing them with an authentic portrayal of the common soldier or civilian during the American Civil War that is based upon research. Some living historians consider a reenactment degrading to the men who fought and sometimes died during the Civil War.

The main difference between a reenactor and a living historian is that a living historian continuously researches different aspects of the American Civil War in order to educate the public, focusing on the roles, uniforms, equipment and mindset of the average Civil War soldier, especially paying close attention to detail of the time period and theater of the Civil War they are portraying. All uniforms, food and camps of a group of living historians have a higher standard of authenticity. They use only items that are documented and made to the exact specifications as the original like you would see in a museum or what the actual soldiers wrote in their letters or dairies. Make no mistake, never call a true living historian a “reenactor” as there is a big difference between the two.

A living historian also understands the importance of interpretation. Without interpretation you would not be able to understand the events of a certain time period, this is lacking when you attend a reenactment. The role of educator would apply to a living historian as they share their research with the public, research that is based upon fact and not secondary sources.

Some of the area’s most authentic living histories are held at the South Mountain State Battlefield near Boonsboro, Maryland. The Battlefield holds an annual event entitled “Fire on the Mountain” which will be held in September of this year, and will feature artillery and infantry demonstrations as well as tours of Fox’s Gap. Events such as “Fire on the Mountain” are very important as it educates people not only to the significance of the Battle of South Mountain, but it also shows people how these soldiers encamped during the Maryland Campaign.

Every year on Labor Day weekend, the Gettysburg National Military Park holds an authentic event that features a full Confederate battery. Last year was my first year participating in this living history demonstration and it was great to be able to educate the public about Confederate artillery. Most spectators that come to this demonstration are surprised to see three original cannon tubes dating back to 1864 that are actually being fired.

For the last several years, I have participated in living history demonstrations on the artillery at Monocacy, Antietam, South Mountain and Harper’s Ferry. The public gains so much from these events, all things that they can not experience at a reenactment. They are up close and personal with the living historians and they can see exactly how the battery, section or piece worked as well as witnessing a detachment of cannoneers working their post.

This year, the Monterey Pass Battlefield Association in Blue Ridge Summit will be conducting a series of educational programs for locals to understand the average Civil War soldier on campaign. Many people are unaware that what you see at a big reenactment is not what the soldiers experienced. We are also planning several living history events to educate the public on their Civil War heritage as well as the area’s Civil War history.

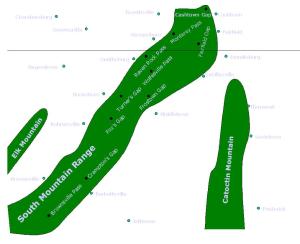

With summer approaching, and the celebration of Bells and History Days behind us, it is a great idea to get out and explore the Civil War related sites in your own back yard. There are so many sites, and these sites offer several educational programs that can be fun for the whole family. Three campaigns entered Maryland during the Civil War. The first is Maryland Campaign and includes the sites of South Mountain State Battlefield, Washington Monument State Park, Antietam National Battlefield, Harper’s Ferry National Park and the C&O Canal National Park which also houses Ferry Hill, the home of Henry Kyd Douglas, who rode with General Stonewall Jackson. This campaign ends with the battle of Shepherdstown, West Virginia.

The Pennsylvania Campaign also includes several sites from South Mountain State Battlefield, Emmitsburg, Gettysburg and Monterey Pass. The 1863 Invasion of Pennsylvania which resulted in the battle of Gettysburg is considered the turning point of the American Civil War. The Retreat from Gettysburg, considered as one major battle, includes the battles of Monterey Pass, Smithsburg, Funkstown, Boonsboro and Hagerstown, all fought from July 4 through July 14.

The last campaign to take place in our area occurred in July of 1864 when General Jubal Early led his corps of Confederate troops through Maryland and came close to taking the Union Capital of Washington. These sites include South Mountain State Battlefield, Monocacy National Battlefield and Fort Stevens, near Washington, D.C.

All of these places are near Emmitsburg and are a great way for the family to experience Civil War history through interpretive programs, living history programs, tours and demonstrations. These parks allow families to take in views of the landscape, which in many instances were written about by Civil War soldiers who traveled through the area. So get out and support your local battlefields, I promise you, you won’t be disappointed.