During the French and Indian War (1754-1763), settlements east of South Mountain had been relatively safe to live in. Then, in the spring of 1758, the Indians and some of their French allies raided the settlements along South Mountain. On April 5, 1758, near modern day Cashtown, Mary Jemison, her parents, and some of her relatives were taken prisoner. She would be the only survivor, as to lighten the load the Indians killed her parents. They would take her to Fort Duquesne where she was sold to Seneca Indians.

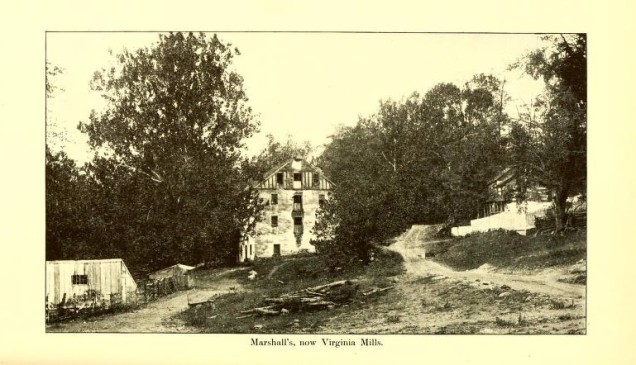

A few days later, another raiding party traveled along the eastern base of South Mountain to the home and mill of Richard Bard. Richard Bard was born in 1736 and lived at the base of South Mountain where he operated a mill at Mud Run with his wife Catherine Poe Bard and their seven month old son. This area today is known as Virginia Mills, and is located on Mount Hope Road, a few miles east of Monterey Pass.

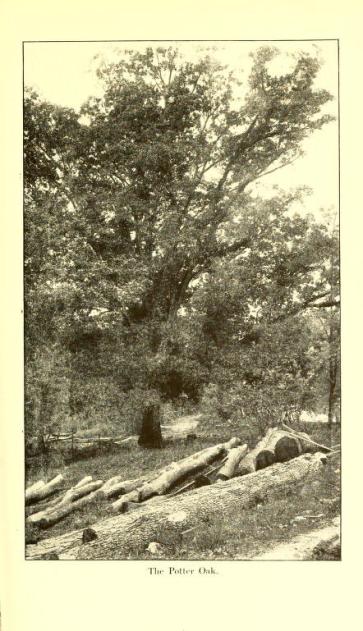

April 13, started like any other day for the Bard family. The Bard family was inside the house entertaining Richard’s cousin Thomas Potter and small children Hannah McBride and Frederick Ferick. Out in the nearby fields working were Samuel Hunter and Daniel McManimy. William White, a young boy, was on his way to the mill for a visit.

Hannah was by the front door, when she saw the indians coming, about nineteen Delaware Indians total. By the time that Bard and Potter knew what was happening, it was too late. The Indians rushed into the house. Potter and one Indian armed with a cutlass struggled for a bit until Potter took the weapon and began striking the Indian, wounding the warrior.

Bard grabbed a pistol and when he went to pull the trigger, it failed to go off. The Indians began fleeing from the house. One of Indians by the door saw what was happening, fired a shot, and wounded Potter. The main door was closed by the Indians. The Bard family knew they were outnumbered and feared that the Indians would fire the house. The Indians surrounded the cabin and forced the Bard’s and their friends to come to terms with a surrender. After working out a surrender, the Bard family and other occupants came out and surrendered.

Hunter and McManimy, who were working in a nearby field, were also captured, including the young boy White. Nine total were captives of the Indians. As the Indians began moving westward over South Mountain, they killed Potter, scalping him. About three or four miles into South Mountain, the young toddler John Bard was speared, repeatedly beaten, and was scalped as well.

The Indians, with their war trophies, moved northward toward modern day Mont Alto Gap. Many deep gorges made the journey difficult. The Bard’s were hungry and tired. The prisoners were not allowed to socialize with one another, and the Indians even went as far as to paint red over Richard’s face. He thought that he would be the next to suffer the hatchet.

The party continued northward along South Mountain, entering the Conococheague Valley near modern day Scotland. The Indians feared the garrison of Fort Loudon several miles to the west. They also feared traveling too close to Fort Chambers and Fort McCord, which were in line of their route. By nightfall, they had moved some forty miles on foot.

The next day, the Bard’s moved through Yankee Gap into Bear Valley, to Horse Valley, and finally Path Valley. During the day, the Indians killed Hunter, sinking the hatchet into his head as he and Bard sat down. Then they scalped him. They moved to Sideling Hill, where they would encamp for the night.

By the third day, the party made it’s way between modern day Huntingdon and Raystown (Bedford). During the day, the Indians held a council on whether Richard should be killed. They painted half of his face red, but he lived on. The fourth day, the Indian raiders and their prisoners were the crossing the Allegheny Mountains. That night, snow fell. The prisoners were not allowed to be near the fire. By now, the prisoners were in dire need of rescue. Certain death was near if they couldn’t get help. Richard’s wife was still mourning the murder of her seven month old boy.

On the fifth day, Richard was beaten badly by one of the Indians and almost disabled, as he was crossing a stream. Realizing that death was so close, Richard still was not permitted to talk to his wife. One of the Indians shot a turkey and ordered the Bard’s to pluck the feathers and clean it out. There, Richard planned his escape to get help after a diversion was made by his wife.

Richard waited for the right moment. That moment came during the late evening when the Indians began dressing themselves in women’s clothing that they had captured along the way. Richard made his way toward a bush and concealed himself inside. HIs wife Catherine, kept the Indians attention on a gown. One of the other Indians noticed that Richard had gone missing.

Richard waited for the right moment. That moment came during the late evening when the Indians began dressing themselves in women’s clothing that they had captured along the way. Richard made his way toward a bush and concealed himself inside. HIs wife Catherine, kept the Indians attention on a gown. One of the other Indians noticed that Richard had gone missing.

The Indians quickly searched for Richard, but came up empty handed. The Indians and their captives made their way to the Allegheny River and to Fort Duquesne. They would remain there for one night before moving twenty miles down the Ohio to an Indian village. There, Catherine was beaten by several of the Indian squaws.

The prisoners were escorted to Kaskaskunk, a village ran by the Glickhickan. There, McManimy was killed after being beaten. The two boys and Hannah were left behind while Catherine was taken to another village. Once there, she would be adopted to replace a dead sister of two Indian brothers. The women who beat her, were punished for their actions.

Catherine was moving with her new Delaware family to the headwaters of the Susquehanna. The journey was painful for her, as she had not recovered from being taken prisoner. She was given a horse to ride upon, until it was used to replace a pack horse that was dying. 500 miles since her capture, she came to her new home, a cabin. The only thing she had to her name was a blanket that was given to her by her captors. Catherine would be forced to learn her adopted native language in order to communicate.

While, Catherine was being adopted, her husband, Richard had a difficult time navigating through the mountains. His feet blistered as his shoes were worn out. He took briars to sew up the deep cuts on the bottom of his feet. He ripped portions of his breeches to wrap around his feet, giving them some type of soles. He was starving, tired, and fatigued.

By the eighth day of his escape, he arrived at Juniata in the evening. Moving through the night, cold and wet, he made his way through the wilderness. The next day, he ran into three Cherokee Indians who escorted him to Fort Lyttleton. Richard Bard was finally saved.

For the next two years, Richard Bard searched for his wife. In 1758, after the fall of Fort Duquesne, Richard Bard headed to the fort to find his wife. At the newly rebuilt Fort Duquesne, now called Fort Pitt, Bard discovered some of the same Indians that were with him on his journey as a prisoner. They threatened to kill him if he came back.

Richard Bard came back to Fort Pitt and found the location of his wife. Bard made arrangements to pay forty pounds for her release. After being held in captivity for two years and five months, she was released and the ransom was paid.

The ordeal had officially come to an end. The Bards would rebuild their lives moving to Williamson in Franklin County, PA. Richard would die in 1799, survived by his wife Catherine. She would die in 1811. They would have four children, all of whom are buried in Church Hill Graveyard, Mercersburg, PA.