During the month of October at Loyalhanna, Colonel James Burd, the garrison commander continued training and organizing troops for the final push toward Fort Duquesne. Colonel Burd also organized the horses, livestock and wagons, along with stockpiles of supplies. Several work details were sent out to improve or clear roads. During the month, heavy rains plagued the area, causing the roadways to deteriorate.

Higher up the British military chain of command, Brigadier General John Forbes tried to keep his Indian allies content and happy, which was a hard task to accomplish. Also, several colonies and British representatives began peace talks with thirteen chiefs of several tribes in the Ohio Country, including the Iroquois, Delaware and Shawnee. These talks were to help ease tensions over the 1737 Walking Purchase.

The Treaty of Easton prohibited the Indians from fighting on the side of the French during the French and Indian War. In return, it returned large portions of hunting land to the tribes in the Ohio Valley. The Treaty of Easton also redefined the colonial settlements west of the Allegheny Mountain after the war. The treaty was signed in late October and would have a huge impact on the French at Fort Duquesne.

On October 16, Colonel George Washington and his Virginian militia arrived at Loyalhanna from Fort Cumberland. These men were welcomed reinforcements. While the troops worked, more supplies arrived, however other supplies, such as clothing and blankets, were in short supply. Colonel Henry Bouquet reported that many of his men needed clothing and equipment before moving out of Loyalhanna to siege Fort Duquesne. Since the battle of Fort Ligonier, most of the horses were taken or killed. This forced the British army to wait for supplies to move in.

Brigadier General Forbes arrived at Fort Ligonier on November 2. He was not pleased with the conditions of the roads, weather and his men. These problems could force him to stall the campaign, and in fact, had already pushed the campaign’s conclusion back an additional month.

On November 11, Brig. Gen. Forbes held a council war with his top field officers and quartermaster. Brigadier General Forbes worried about the condition of his army and size of the French garrison he was assigned to attack. Brigadier General Forbes decided that the campaign could not go any further, as winter was about to set in. He made the decision to remain at Fort Ligonier for the winter.

A day later, a 40 Marine French detachment and 100-200 man Indian raiding party was spotted near Loyalhanna. Brigadier General John Forbes ordered Colonel Washington’s 1st Virginia Regiment and Lieutenant Colonel George Mercer’s 2nd Virginia Regiment out to meet the threat. As Lt. Col. Mercer was getting into position, Colonel Washington’s men were on the move in the fog. They heard movement, thinking it was the French and fired into Lt. Col. Mercer’s regiment.

During the exchange, Colonel Washington lost control of the skirmish due to weather conditions. The skirmish was a tactical defeat for the Virginians, resulting in two officers and thirty-eight men killed or wounded. A couple of French prisoners were taken. Brigadier General Forbes was outraged with Colonel Washington’s performance, which showed that the Virginians had much to learn with regard to discipline. Why, Brig. Gen. Forbes didn’t choose from the regulars that made part of the 4,000 men garrisoned at Loyalhanna for this task is not known.

On November 13, Brig. Gen. Forbes oversaw the interrogation of the prisoners, and conducted the interrogation personally. One of the prisoners was Richard Johnson, an Englishman captured a few years prior. During the interrogations, Brig. Gen. Forbes began gathering intelligence about Fort Duquesne. He quickly learned that the French were running low on food and manpower. Many of the Indians left due to the Treaty of Easton being signed, which Brig. Gen. Forbes had a huge role in. He also learned about the layout of the French fort. As he gathered information, he quickly countermanded his decision to stay at Loyalhanna for the winter. If he was going to strike Fort Duquesne, this was the perfect time to do so.

His army was quickly reorganized, and would begin moving out on November 14, although some sources state it was the day after. The organization of Forbes’ army was broken and organized into four brigades. First Brigade was commanded by Colonel Bouquet, and consisted of the Pennsylvania Provincials and the Royal Americans. Second Brigade, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Montgomery, consisted of the Highlanders and the 2nd Virginia Regiment. Brigadier General Forbes accompanied this brigade. Third Brigade was commanded by Colonel George Washington and consisted of the 1st Virginia Regiment, North Carolina Battalion, Lower Counties Battalion and the Royal Maryland Battalion. It also consisted of two companies of artificers and two field artillery trains.

The Fourth Brigade was under the command of the garrison commander, Colonel Burd, who remained behind. The garrison command consisted of several hundred men from various regiments and battalions. They were ordered to forward supplies needed for the march, and to provide protection for Forbes’ army if they came under attack by means of a fall back position. The men were ordered to march light and limit what they carried.

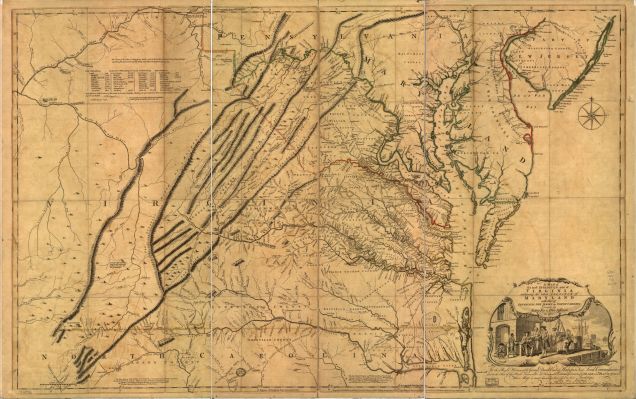

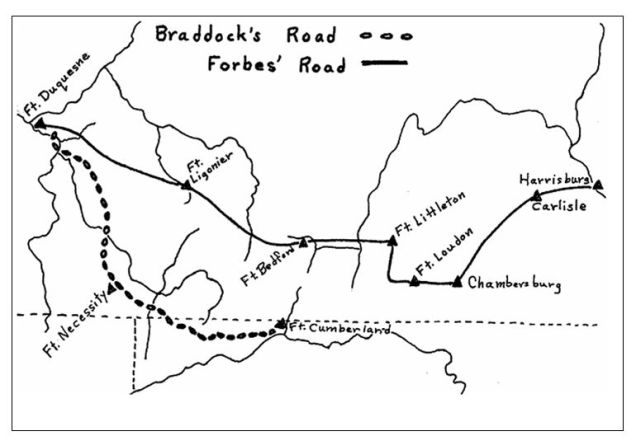

As the three main brigades moved out of Loyalhanna for the forty-seven mile trek to Fort Duquesne, they would maneuver by leap-frogging by brigade. Flankers would also be heavily used once past Chestnut Ridge. To avoid traffic congestion, each battalion within the brigade would march at various times of the day, staggering their movements. Entrenchments were to be built at the end of the day at the various camp locations. Brigadier General Forbes wanted to make sure that the mistakes of Major General Braddock were not repeated.

At 8:00 a.m. on November 15, the first portions of the British army moved out of Loyalhanna. One major natural barrier remained in Brig. Gen. Forbes way. This was Chestnut Ridge, the location of Grant’s Delight. Once past Chestnut Ridge, the valley floor, along with a few smaller ridges were what remained. Brigadier General Forbes would march along the ridge line of Chestnut Ridge, and then march down into the valley.

By November 19, Colonel Washington had marched to Turtle Creek while Lt. Colonel Montgomery was marching out of Loyalhanna. Brigadier General Forbes’ army stretched over thirty miles. On November 21, Colonel Washington was cutting in the road leading to Fort Duquesne. The next day, he held the advance at his camp until the main portions of British army began marching in.

On November 23, Brig. Gen. Forbes’ entire army was massed in Colonel Bouquet’s camp, located twelve miles from Fort Duquesne. It was here that Brig. Gen. Forbes changed his marching orders. Instead of marching the rest of the way by brigade, he ordered his army to march in column.

While the British were on the move, their movements did not go unseen by the French. The French commander at Fort Duquesne, Captain Ligonry, knew of the British advance and had several decisions to make. The main decision was to stay and fight or evaluate the garrison. The French and Indian War was beginning to turn in favor of the British, as other campaigns were taking place, the garrison at Fort Duquesne was reduced to garrison other fortifications in the Ohio Country. Because of this, Fort Duquesne was being cut off from support.

On November 24, the British army begins it last movement to Fort Duquesne. By the time the French fort was in view, the British saw smoke rising from it. The French had set fire to the fort and left without a fight. But for Brig. Gen. Forbes, he would have to wait one more night before entering the charred remains of the fort.

At daybreak on November 25, Brig. Gen. Forbes marched his army toward the fort, and by the afternoon, he officially took the fort. Brigadier General Forbes accomplished his objective without a major battle. Young Colonel Washington walked into the remains of Fort Duquesne, the same fort that he tried to take in 1754, with Braddock, for the same objective in 1755 when his army met disaster. Now, the Forks of the Ohio was under British control.

By November 28, detachments of British soldiers were sent out to bury the dead from Grant’s defeat that occurred several weeks prior. The bodies of the dead still littered the battlefield. Some troops, including Major Francis Halkett, ventured out to Braddock’s Field. There, Major Halkett was able to locate the remains of his brother and father and provided them with a proper burial.

Brigadier General Forbes ordered the construction of a new fortification and named it Fort Pitt. Colonel Huge Mercer was placed in command of the garrison. He also named the Loyalhanna fort, Fort Ligonier, and the fort at Ray’s Town, Fort Bedford.

As Brig. Gen. Forbes’ health quickly deteriorated, he wasn’t able to stay at Fort Pitt for long. By early December, he began making his way back to Philadelphia. As he was laid upon his stretcher, he was now headed back to the east, and would gaze on the mountains that he tackled one last time. Brigadier General John Forbes died on March 11, 1759. He is buried inside the Christ Episcopal Church and Churchyard, Philadelphia.