On June 28, Maj. Gen. Braddock’s army was located at Stewart’s Crossing on the Youghiogheny River. The British would actually cross this river a couple of times as they marched west and north to Fort Duquesne, where they would encamp for a day. During the day, rain fell across the region, adding to the misery in the wilderness. The next morning, on June 30, Braddock forded the river, which was about 200 yards wide. Crossing the river was not an easy task, and often the British were outin the open, in full view. The advance guard was ordered over first to secure the opposite side of the river. Once secured, the artillery and wagon trains were next to cross, followed by the rest of the army. Camp was established to give time for the road workers to open the new road.

On June 28, Maj. Gen. Braddock’s army was located at Stewart’s Crossing on the Youghiogheny River. The British would actually cross this river a couple of times as they marched west and north to Fort Duquesne, where they would encamp for a day. During the day, rain fell across the region, adding to the misery in the wilderness. The next morning, on June 30, Braddock forded the river, which was about 200 yards wide. Crossing the river was not an easy task, and often the British were outin the open, in full view. The advance guard was ordered over first to secure the opposite side of the river. Once secured, the artillery and wagon trains were next to cross, followed by the rest of the army. Camp was established to give time for the road workers to open the new road.

By July 2, Maj. Gen. Braddock was well into hostile territory. As the men marched, they noticed that coal was in abundance, lying on top of the ground. The area was also a swamp, and because of that the army encamped at Jacob’s Creek to allow bridges to be constructed for the army vehicles. The men also faced a new challenge. Rations were running low and had to be cut back until fresh supplies were brought up from the rear. Rations then consisted of bacon and flour. Colonel Thomas Dunbar was several days behind Braddock’s flying column due to the conditions of the roads and trying to move the heavier artillery and wagon loads of supplies.

The next day, on July 3, Braddock met with his officers regarding Colonel Dunbar’s men. Several officers had wondered if they should wait for the Colonel Dunbar to arrive and concentrate the two columns into one since Fort Duquesne was a few days march ahead. The vote was cast and it was decided that the flying column would continue moving ahead without Dunbar’s troops. As Braddock’s flying column encamped, pickets were ordered out, and were to be doubled up for security measures.

By July 6, camp was located at Monacatootha, roughly three to four days march from Fort Duquesne. For the past several days, the British had no contact with the natives or the French, and moved unopposed through the American wilderness. After being ordered to stall the British advance, the French, Canadian and Indian allies had not slowed Braddock’s advance.

On July 7, trying to avoid the Turtle Creek Narrows, Braddock’s column turned north. This detour would cause him to lose a day. After encamping at Turtle Creek, Braddock marched all day and well into the evening, coming to a halt at Sugar Creek at 8:00 p.m. As the British marched throughout the day, the French and their Indian allies at Fort Duquesne were rallying to attack. French Captain Louis L. Beaujeu rallied alongside his Native allies. Hundreds of Natives encamped just outside of the fort and planned to move out the next day, searching out Braddock’s army.

At 2:00 a.m. on July 9, Braddock’s army began forming up for the final push to Fort Duquesne. Major General Braddock’s plan was to hurry out and began laying siege on the French fort. Twenty-four rounds of fresh ammunition as well as two days rations were issued out to the 1,400 men in the flying column. The advance guard, under Captain Thomas Gage, was first to move out at 2:00 a.m. Following behind, two hours later, was the work detail under Major Sir John St. Clair. The main body under Maj. Gen. Braddock moved out at 5:00 a.m., with the rear guard moving out shortly thereafter.

The first of two Monongahela River crossings came into view. The advance guard and two 6-pound cannon forded the river, which was about knee deep and 200 yards wide. Once across the steep banks, the advance guard secured the river crossing. The work details soon came to the road, but for Braddock, the workers cutting in the road were moving too slow.

By 8:00 a.m., Braddock had reached the first river crossing. There, he reformed his units and moved forward. About four hours later, Braddock’s men had come to the second river crossing. Major General Braddock suspected that the enemy was watching his every move, as the river crossing was in a very exposed place. With the king’s colors and music playing “The Grenadiers March,” the men began to ford the Monongahela River in tight formation with bayonets gleaming. Never before had America witnessed such display of military might.

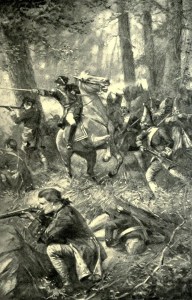

At 8:00 a.m., 254 French soldiers and Canadian militia and roughly 600-700 Indians under the command of Captain Jean-Daniel Beaujeu left Fort Duquesne. They moved out following the path that led to the Monongahela River crossing. Around 1:00 p.m., as the British were moving forward, the French, French Canadians, and their Indian allies were caught off guard seeing Braddock’s men so close. Captain Beaujeu quickly organized a frontal attack and sent the Indians to ambush the British flanks.

Major General Braddock’s army was about 1/8 of a mile wide with flankers and about one mile in length strung out. Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Gage and his advance guard were ahead of Braddock’s flying column, and received word from a guide that the French were approaching. With very little time, Gage began preparing for the pending battle. Gage quickly ordered bayonets to be fixed, and the British battle line moved forward.

The French Marines fired a volley at Gage’s men, which was quickly answered by the British. After a short exchange, the French Marines and Canadian militia began to fall back as Gage’s men tried taking a hill on their right flank. As Captain Beaujeu was rallying his men and reorganizing his command, the British fired a third volley, killing Captain Beaujeu.

The French Marines fired a volley at Gage’s men, which was quickly answered by the British. After a short exchange, the French Marines and Canadian militia began to fall back as Gage’s men tried taking a hill on their right flank. As Captain Beaujeu was rallying his men and reorganizing his command, the British fired a third volley, killing Captain Beaujeu.

French command fell upon Captain Dumas, who rallied his men just as the Indians were beginning their attack, hitting the British flanks. The French battle formation was now taking on the shape of a half moon. Once the British flanks came under fire, the advance guard’s battle line became compromised, and they fell back, causing a great deal of confusion. The Indians had taken positions behind fallen trees on the British right flank, and kept up a severe fire hitting their left flank.

Hearing the sounds of the battle ahead, St. Clair quickly ordered his two 6-pounders to be readied, and for the workers to form ranks. The artillery threw grape shot though the woods, tearing up the landscape in its front. The cannons provided aid to Gage’s men during the second attack, but were exposed once the advance guard fell back onto St. Clair’s line, causing more confusion. At the same time, a half mile away, Braddock also heard the sounds of what might be a battle unfolding and thought perhaps that this was another false alarm. During the confusion, St. Clair was struck in the right lung and began riding back to find Maj. Gen. Braddock, where he collapsed.

Standing next to his artillery with his aides, the Royal Naval Detachment, and Virginia horsemen, Braddock was quickly met by members of his staff including George Washington. With the battle going into its fifteen to twenty minute mark, Braddock rode forward, along with several mounted Virginian horsemen to see what was in his front. Arriving on scene, Maj. Gen. Braddock saw men falling all over the place. Many were in a panic stricken state of mind. Several British soldiers were wounded or killed by friendly fire.

Maj. Gen. Braddock ordered the wagons and artillery to be secured, and at the same time, he ordered the 500 men marching on both sides of the wagons to quickly move forward. This left Colonel Halkek with 250 men to guard the wagons. The Indians moved to the rear of Braddock’s column, where the wagons were located, and began attacking them. At the same time they continued putting pressure on the flanks of the British. The half moon battle tactic never took on a full circle, which was most likely the only thing that saved the British from being completely destroyed. During this portion of the fight, Colonel Halket was killed and his son, Lieutenant James Halket fell wounded upon his father’s chest.

While Braddock was commanding the field, many of the Colonial troops began taking positions in the same manner as the Indians. At one point, Colonel George Washington suggested to Braddock that he order men to take cover behind the trees, but Maj. Gen. Braddock cursed the idea as being cowardly. As Maj. Gen. Braddock rode back and forth, the scene became worse. Many of the British troops, who were earlier issued twenty-four rounds of ammunition, were running low and began empting the cartridge boxes of the dead and wounded.

Many men were still trying to take to higher ground on their right, but were not able to, as the firing came from their front, flanks, and rear. Eventually Lt. Col. Gage fell wounded upon the battlefield. This caused more troops to panic and fall back onto more oncoming British troops. During the confusion, Maj. Gen. Braddock had four horses shot out until a bullet hit his arm and entered into his lung.

Not long after Maj. Gen. Braddock was wounded, the British and Colonial troops broke. The trouble began with the wagoneers, and soon after the army was in flight. By 5:00 p.m., most the shattered remains of Braddock’s flying column were hastily headed to the Monongahela River crossing. Lieutenant Robert Orme, along with Washington, and Captain Robert Stewert carried the wounded Braddock to safety. As the British retreated, the Indians and French followed suit. By the time that the British made it to the other side of the river, the Indians and French began looting what the British had left behind in the wagons.

Not long after Maj. Gen. Braddock was wounded, the British and Colonial troops broke. The trouble began with the wagoneers, and soon after the army was in flight. By 5:00 p.m., most the shattered remains of Braddock’s flying column were hastily headed to the Monongahela River crossing. Lieutenant Robert Orme, along with Washington, and Captain Robert Stewert carried the wounded Braddock to safety. As the British retreated, the Indians and French followed suit. By the time that the British made it to the other side of the river, the Indians and French began looting what the British had left behind in the wagons.

Out of less than 1,500 British soldiers and Colonials at the battle, 456 were killed, 421 were wounded, and many more were captured. Other resources state that the British casualties were much higher. The French suffered far less with about 30 killed, and 57 wounded. The shattered British army retreated to Colonel Dunbar’s camp, west of Great Meadows, arriving there on July 11. There, most of the supplies were destroyed to lessen the baggage so that the army could fall back to Fort Cumberland for a faster retreat.

During the evening on July 13, near Great Meadows, Braddock had called upon Colonel George Washington and asked him to oversee his burial. Shortly afterward, Braddock died. The next morning, Maj. Gen. Braddock was placed into a hasty coffin and buried in the middle of the road.

During the evening on July 13, near Great Meadows, Braddock had called upon Colonel George Washington and asked him to oversee his burial. Shortly afterward, Braddock died. The next morning, Maj. Gen. Braddock was placed into a hasty coffin and buried in the middle of the road.

The British continued their march, arriving at Fort Cumberland on July 17. Although the French did not pursue the British, Colonel Dunbar, now commanding the army, fell back to Philadelphia after he realized that he had no resources at his disposal to launch an attack to take Fort Duquesne.